Asset Management

- Home

- Asset Management

Azurelope assist large clients in public sector with the development of an Enterprise Asset Management vision. We have first hand knowledge and a full understanding of how to deliver a project of this complexity and are engaged with multiple clients in regulated industries such as nuclear, defence, rail and local government. We develop scalable open cloud-based architectures using the latest software engineering industry best practice.

Azurelope are a vendor of enterprise level SaaS products such as our flagship product REBIM for engineering asset management.

Through our experience with other clients we have been able to demonstrate significant cost reductions to operating budgets by eliminating costly and unwieldy legacy systems and processes in a staged and managed way by implementing our asset management software REBIM. Through our own research, we understand there to be at least 20% waste as engineers search for information on legacy systems. One particular client of ours has identified through their own studies a minimum of 25% wasted engineer’s time through using multiple systems to understand assets.

Our technology manages asset attributes and workflow by utilising a standard data models, using a logical hierarchy of tags based on a mix of GIS, OpenBIM and system engineering principles. This standard data model allows us to organise and identify all assets at enterprise level and to retrieve this data by various different ‘aspects’.

Digital Asset Lifecycle

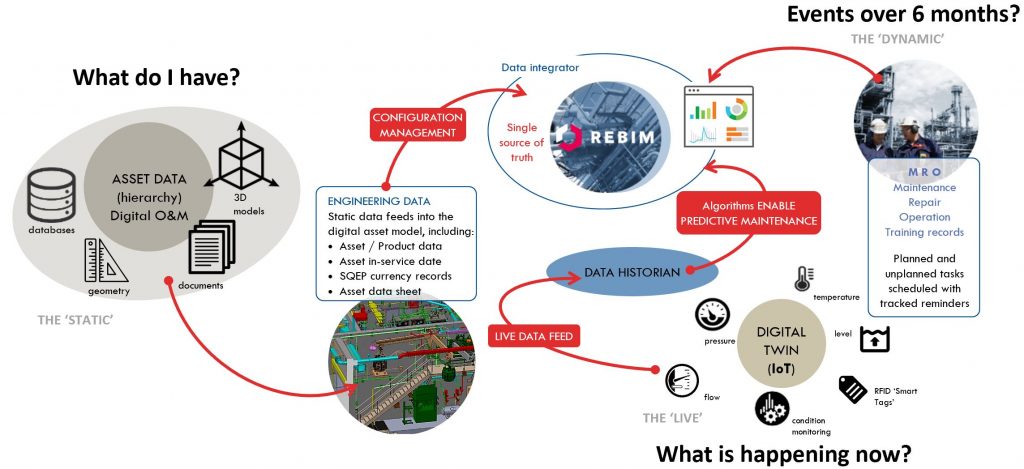

Enterprise Asset Management relies on establishing an enterprise data model that can facilitate the persistence of all of an organisation’s assets represented as asset tags in a logical hierarchy

This logical hierarchy often known as a Plant or System Breakdown Structure is used to bind all other data objects as children of the assets. Using a series of asset tags and events (things that happen to an asset over it’s lifecycle) in a central digital environment is key to delivering the insights needed to make key decisions

With our REBIM platform, we are able to deliver significant organisational benefits including:

- The removal of wasteful activities and administration processes through the implementation of our real-time asset tracking system

- Complete tracking of planned and unplanned maintenance events for all organisational assets

- The delivery of a single corporate solution for asset management which will remove the need for duplicate systems that perform similar functionality in separate areas

- Single collaborative environment to engage with the engineering supply chain with full approval workflows for project deliverables.

- Automation of value activities is something that, although to date we have not focussed specifically we are confident our condition reporting management knowledge and trend analysis can be applied to the area of route optimisation to establish and plan the most appropriate routes for value activities.

- A vast reduction in, and potentially the elimination of, preventable demand by providing access to all stakeholders a system with intuitive navigation and processes

- Enable frontline staff to close work as soon as the work is complete through our REBIM ecosystem

- Simplify the process of work administration by utilising the process of attaching workload, tasks and processes to the asset in question and viewing progress and history through the same asset.

Enterprise Asset Management

ISO 55000 compliant digital asset management

Total Cost of Ownership

Understand whole life cost of your assets

Business Analytics

Leveraging data for informed decisions

Supply Chain Collaboration

Mobile technology for supply chain management

Supply Chain Collaboration

- Mobile task allocation and management

- Work order management for routine and urgent maintenance

- Supply chain quote management

- Real-time discussion between internal staff and the supply chain via mobile technology

Total Cost of Ownership

- First Cost (FC)

- Lifecycle Costing (LCC)

- Total Cost of Ownership (TCO)

- Enterprise Cost Model (ECM)

For a typical built asset, the TCO would need to factor in costs accumulated from purchase to decommissioning. For example, this means initial acquisition price (design / build install), commissioning, repairs, maintenance, upgrades, service or support contracts, integration, security, software licenses, user training, upgrades, decommissioning and disposal. It can even include the credit terms on which the company purchased the asset. Through analysis, the purchasing manager might assign a monetary value to intangible costs, such as systems management time, electricity used, downtime, insurance and other overhead. The total cost of ownership must be compared to the total benefits of ownership (TBO) to determine the viability of a purchase.

There are several methodologies to calculate total cost of ownership, but the process is not perfect. It can be difficult to define a singular methodology for basing purchasing decisions on uniform information. There are also unforeseeable costs that can distort the model such as a vendor refusing to continue to provide availability of spares. Unpredictable costs can also include sudden rises in price in spares and consumables or rises in raw material commodities.

Another problem is that it is difficult to determine the scope of operating costs for any piece of equipment; some cost factors are easily overlooked or inaccurately compared from one piece of equipment to another. For example, do support costs include the cost of spare parts? This might make support cost more than it does on an equivalent piece of equipment, but eliminates an additional cost factor of parts acquisition.

Owner / Operators and purchasing decision makers complete total cost of ownership analysis for multiple options, to then compare TCOs to determine the best long-term investment.

Read more on the True Cost of Ownership here at the REBIM Blog.